Why Galvayne’s Groove Is Letting You Down: Smarter Ways to Age Horses Using Their Teeth

For decades, Galvayne’s Groove has been held up as a standard reference point for aging horses by their teeth – taught in vet schools, shared among practitioners, and repeated in textbooks without much question.

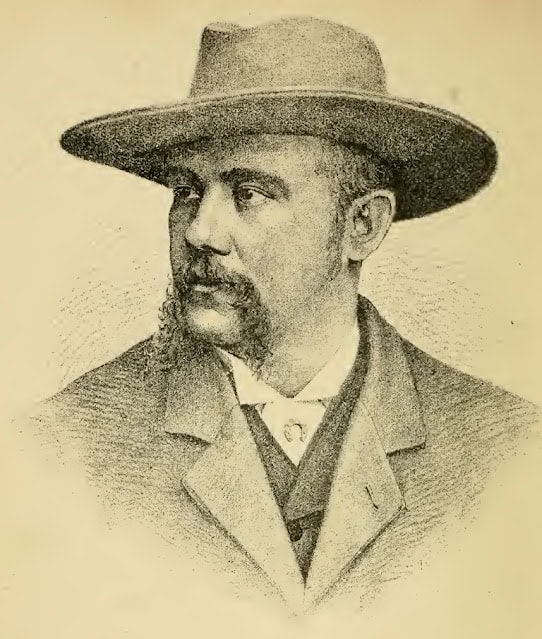

But here’s the truth: Galvayne’s Groove is one of the least reliable indicators we have. Sydney Galvayne (1846–1913) was a prominent Australian horseman whose fame spread widely through his books and public demonstrations of horse ageing. Reports suggest he planted helpers in the audience to “volunteer” a horse for ageing—and, naturally, they backed up his theatrical conclusions.

Yes, it tends to show up around 9 or 10 years of age. But after that? Anything goes. Some horses never develop the ‘standard’ look. Others show staining that looks like it.

And the classic “halfway down by 15, all the way by 20, gone by 25” rule? It’s more folklore than fact.

As veterinarians, we need better tools. Because knowing how to age a horse using teeth isn’t just about curiosity, it affects nutrition, management, training expectations, and client communication.

If you get it wrong, everything that follows is off the mark.

In this article, we’ll look at:

- Why Galvayne’s Groove is often misleading

- Which incisor-based aging methods are more accurate

- What to watch for on the occlusal surface, gingival margin, and tooth profile

- And how to group horses into realistic age brackets with confidence

If you’ve ever felt unsure while aging a horse, or just want to get better at it, this is for you.

Let’s drop the myths and start aging horses the right way.

The Problems with Galvayne’s Groove

Ask any equine veterinarian how to estimate a horse’s age, and Galvayne’s Groove is bound to come up. It’s been printed in guides, scribbled on whiteboards, taught at Pony Club and 4H level and passed along as gospel.

But if you’ve ever relied on it in practice, you’ve likely had that moment where it just doesn’t add up.

And that’s because it often doesn’t.

The idea is simple: a dark groove appears on the upper corner incisor (tooth 103 or 203) around 10 years of age, reaches halfway down by 15, fully extends by 20, and starts to disappear by 25. But in reality, Galvayne’s Groove:

- Doesn’t appear at all in some horses

- Shows up earlier or later in others

- Can be mimicked by staining or surface defects

- Often progresses irregularly – or not at all

In short, it’s inconsistent. And when it’s used in isolation, it can lead to grossly inaccurate age estimations, sometimes off by five years or more.

Dr. Cleet Griffin, in our Dentistry Program (Module 1), puts it plainly:

“I think the most accurate thing you can say about Galvayne’s Groove is that it usually starts to appear around 9 to 10 years. After that, it’s a mess.”

Even if the groove is present, relying on its depth or length can steer you wrong. That’s why experienced equine veterinarians rarely use it as a primary indicator.

Instead, they treat it as one small clue, and not the answer.

If you want to age horses using their teeth more accurately, you need more reliable markers. And that’s where functional, observable changes in incisor shape and wear patterns become far more valuable.

Let’s look at what actually works.

A Better System: Practical Tools That Actually Work

If Galvayne’s Groove has taught us anything, it’s that aging a horse takes more than spotting a single groove.

The good news is there are more accurate, consistent methods available – ones that are grounded in tooth anatomy, eruption patterns, and wear-related changes you can actually see and measure.

Here are the markers we teach in Modules 1–3 of the Dentistry Program – and use in practice every day.

Length-to-Width Ratio of the Upper Corner Incisor (I3 / Tridian 103 or 203)

This is one of the most reliable visual indicators in equine incisor aging, and it’s easy to apply in the field.

- Wider than tall = typically 5–9 years old

- Equal height and width = around 10–15 years

- Taller than wide = 15 years and older

Measure the width across the gumline, not the occlusal surface, and compare it to the visible crown height on the distal aspect.

“Long in the tooth” wasn’t just a saying – it’s anatomically true.

Shape of the Occlusal Surface on the Lower Central Incisors (301/401)

This is another consistent age indicator – if you know what to look for.

- Oval = under 10 years

- Round = 10–13 years

- Triangular = 14–16 years

- Biangular/narrowed = 17+ years

Look at the central incisors only, as lateral incisor shape can be less reliable due to variation.

Presence or Absence of Cups and Dental Stars

This is classic, but still useful when applied correctly. In the olden days unscrupulous horse dealers would perform ‘bishoping’ on lower incisors, creating the illusion of cups (common term for infundibula) in older horses, making them appear younger than they actually were.

Dental star (secondary dentin) appears:

- I1: ~6 years

- I2: ~7 years

- I3: ~8 years

Cups disappear:

- I1: ~7 years

- I2: ~8 years

- I3: ~9 years

These transitions vary with diet and soil type (abrasion plays a big role), so use them as rough guides, especially when backed up by other indicators. A common trap is mistaking cups for the dental star and vice versa. A simple rule of thumb is that in a horse over roughly 10 years of age, if there is only one ‘structure’ visible on the occlusal surface, it will always be the dental star. In a horse under 6-7 years of age, if there is only one structure visible on the occlusal surface, it will be the cup. If there are two structures visible, these will be both the cup and dental star.

Gingival Margin Drop of Central Incisors

As horses enter their teens, the gingival margin of the central incisors begins to recede compared to the intermediates.

By ~12–14 years, this subtle “size drop” becomes noticeable. It’s a good tie-breaker if other features are ambiguous.

Angle of Incisor Occlusion

Younger horses have a nearly vertical incisor angle in profile. As they age, this angle becomes more acute.

By ~20 years, the profile often looks sloped or “tipped back.” It’s not precise, but it helps classify horses into older age brackets.

No single method is perfect. When used together, these tools can give you a much more accurate and clinically useful estimate than any groove ever will.

And they’ll hold up to client questions, case notes, and rechecks far better than saying, “It looked about 15.”

Number of Cheek Teeth

Want to know how to tell the difference between a well grown one-year old and a stunted two year old? Count the number of cheek teeth. Obviously this is more involved than just looking at the incisors. The first molar tooth (the Tridian 09 tooth) erupts in most breeds at one year of age, so a one year old might only have 3 cheek teeth (the premolars) yet a 2 year old will have 4 cheek teeth (3 premolars and 1 molar tooth).

Context Matters: What Affects Equine Tooth Wear and Aging Accuracy

No matter how skilled you are, aging horses by their teeth is never exact. And it’s not because the tools don’t work, it’s because horses don’t live in a vacuum.

Even the most accurate horse aging methods can be thrown off by environmental and individual variation. That’s why we teach veterinarians to use age ranges, not single numbers, particularly in horses over 10.

Here’s what can influence how those incisors wear, and why two 12-year-olds might look five years apart in age according to the dentition:

1. Diet and Soil Abrasion

Horses grazing on sandy or gritty pastures will wear their teeth more rapidly. You’ll see cups disappear earlier, dental stars appear sooner, and even tooth shortening that mimics senior profiles in middle-aged horses.

Conversely, horses on soft forage or hay-based diets may retain more youthful dental features well into their teens.

2. Malocclusion and Jaw Alignment

Class II (overbite) and Class III (underbite) malocclusions distort the incisor table, alter attrition patterns, and make surface shape unreliable. If the incisors aren’t meeting normally, age-based shape changes can’t be trusted.

Always assess the overall alignment before making any assumptions.

3. Workload and Tooth Use

High-performance horses chewing processed feed (especially with treats, or cubes, may exhibit reduced wear (contrary to the name, ‘hard’ feed is actually softer than grass or hay), and horses kept almost exclusively on hard feed and hay will have very little staining of the dental star due to a lack of pigment from fresh grass staining the secondary and tertiary dentine.

4. Breed and Body Size

Breed differences do play a role. Draft breeds and ponies, in particular, often have slightly different eruption timing and wear rates than light horses.

So don’t rely on reference charts alone – use what’s in front of you and take the whole horse into account.

5. Missing or Extracted Teeth

Once a tooth is lost, the arcades shift (this is called mesial drift). Wear patterns can change within months. So if a horse is missing an incisor or has had dental extractions, your best tools may no longer apply.

These are the cases where grouping by age range – 5–10, 10–15, 15+ becomes critical.

Aging a horse accurately means combining incisor landmarks with real-world awareness.

So yes, you can learn how to age a horse using teeth – but you also have to learn when to trust what you’re seeing, and when to back off and say, “This horse is likely somewhere in this range.”

And that’s not guesswork. That’s experience.

Putting It Into Practice: What You’ll Learn Inside the Dentistry Program

If you’ve ever looked at a horse’s mouth and second-guessed the age you gave the owner – you’re not alone.

The truth is, aging horses by their teeth isn’t something you master from a diagram or a single chart. It takes hands-on practice, clinical context, and knowing how to pull together multiple clues – especially once the horse is over five.

That’s exactly what we cover in Modules 1–3 of our Equine Dentistry Program, including:

The Foundations

- Eruption timelines for deciduous and permanent dentition

- How to tell if a tooth is permanent or still deciduous

- Easy-to-remember patterns (2.5, 3.5, 4.5, 5) that help you accurately age horses under five

- Why you can’t trust Galvayne’s Groove, and what to use instead

Age Grouping by Tooth Shape and Wear

- Assessing incisor length-to-width ratios (what’s “long in the tooth” actually looks like)

- Occlusal surface transitions: oval → round → triangular → biangular

- Using cups and dental stars properly, without relying on them alone

- Recognising the gingival margin shift and incisor angulation in older horses

Applying What You See

- Real clinical cases with unknown ages

- How to age with confidence, even when you don’t have a full dental history

- Interpreting wear with diet, environment, and occlusion in mind

- Aging as a diagnostic tool, not just a label

If you want to get better at how to age a horse using teeth – not just in theory, but in practice – this is the training built for you.

You’ll leave with a system. A process. And a level of confidence that puts vague guesswork and outdated grooves firmly in the past.

Because “about 15” isn’t good enough anymore.

Frequently Asked Questions: Aging Horses by Their Teeth

These FAQs are written for qualified equine veterinarians and assume familiarity with Triadan numbering, basic dental anatomy, and routine oral examination.

What is Galvayne’s Groove in the horse?

Galvayne’s Groove is a longitudinal discoloration or surface groove that may develop on the labial aspect of the maxillary corner incisor (Triadan 103/203). Historically, it has been used as an age indicator, with traditional timelines suggesting predictable appearance and progression. In practice, its development and reliability are highly variable.

Why is Galvayne’s Groove considered unreliable for aging horses?

Galvayne’s Groove lacks consistency and repeatability. Clinically, it may:

- Appear earlier or later than expected

- Progress unevenly or incompletely

- Be absent altogether

- Be mimicked by staining, enamel defects, or surface wear

When used as a primary indicator, it can result in age estimates that are inaccurate by several years. As such, it should never be relied upon in isolation.

At what age does Galvayne’s Groove typically appear?

In many horses, some degree of groove or discoloration may be observed around 9–10 years of age, but this timing is highly variable. Absence of the groove does not exclude this age, and presence does not reliably define it.

Should Galvayne’s Groove be used at all in clinical age estimation?

If used, Galvayne’s Groove should be treated only as a secondary or supportive observation, and only if it aligns with more reliable incisor-based markers. Experienced clinicians do not use it as a primary determinant of age.

What incisor features are more reliable for aging adult horses?

More consistent and clinically useful indicators include:

- Occlusal surface shape changes of the lower central incisors (Triadan 301/401)

- Length-to-width ratio of the maxillary corner incisor (103/203)

- Presence and position of dental stars (secondary dentin)

- Loss of cups (infundibula) interpreted cautiously

- Changes in incisor angulation and facial profile

Used together, these provide a far more defensible estimate than any single marker.

How does occlusal surface shape change with age?

The occlusal surface of the lower central incisors (301/401) typically progresses as follows:

- Oval (younger adult)

- Round (mid-age)

- Triangular (older adult)

- Narrowed or biangular (senior)

This progression is influenced by wear and should always be interpreted alongside other findings.

How reliable are cups and dental stars for aging?

Cups and dental stars can be useful contextual indicators, but their timing is strongly influenced by diet, soil abrasiveness, and management. They should support — not dictate — age estimation, particularly in horses over 10 years.

Can pulp exposure be mistaken for cups?

Yes. Pulp exposure or secondary dentin changes may be misinterpreted as infundibular remnants if the examiner is not careful. Differentiating between cups and pulp-related features is essential to avoid significant age underestimation.

What role does the length-to-width ratio of the corner incisors play?

The visible crown height relative to width of the maxillary corner incisors (103/203) is one of the more repeatable visual indicators:

- Wider than tall → younger adult

- Approximately equal → mid-age

- Taller than wide → older adult

Measurements should be assessed at the gingival margin, not the occlusal surface.

Why do horses of the same age often look dentally different?

Incisor wear and appearance are influenced by:

- Diet and soil abrasiveness

- Occlusal alignment and malocclusion

- Missing or extracted teeth (mesial drift)

- Individual chewing behaviour

- Breed and body size differences

As a result, dental aging becomes progressively less precise with increasing age.

How accurate is dental aging in adult horses?

Accuracy decreases significantly after approximately 5–7 years of age. Beyond this point, dental examination supports age ranges, not precise chronological estimates. This is normal and should be communicated clearly in clinical records and client discussions.

How should age be reported clinically?

Best practice is to report age as a range or category (e.g. young adult, mid-age, older adult, senior), particularly in horses over 10 years. This reflects biological reality and reduces the risk of overconfidence or misrepresentation.

Can dental aging still be useful if it isn’t exact?

Yes. When applied correctly, dental aging:

- Informs nutrition and management decisions

- Helps contextualise performance expectations

- Supports welfare assessments

- Improves consistency in clinical reasoning

Its value lies in classification and context, not numerical precision.

Why has Galvayne’s Groove persisted in teaching despite its limitations?

Historically, Galvayne’s Groove offered a simple, memorable rule at a time when better diagnostic frameworks were lacking. Modern equine dentistry education increasingly recognises that simplicity does not equal accuracy, particularly when clinical consequences are involved.

Where can veterinarians learn a structured, reliable approach to dental aging?

A reliable approach is best learned through case-based, veterinary-specific education that integrates eruption patterns, incisor morphology, wear, and clinical context – rather than relying on isolated charts or traditional rules of thumb.